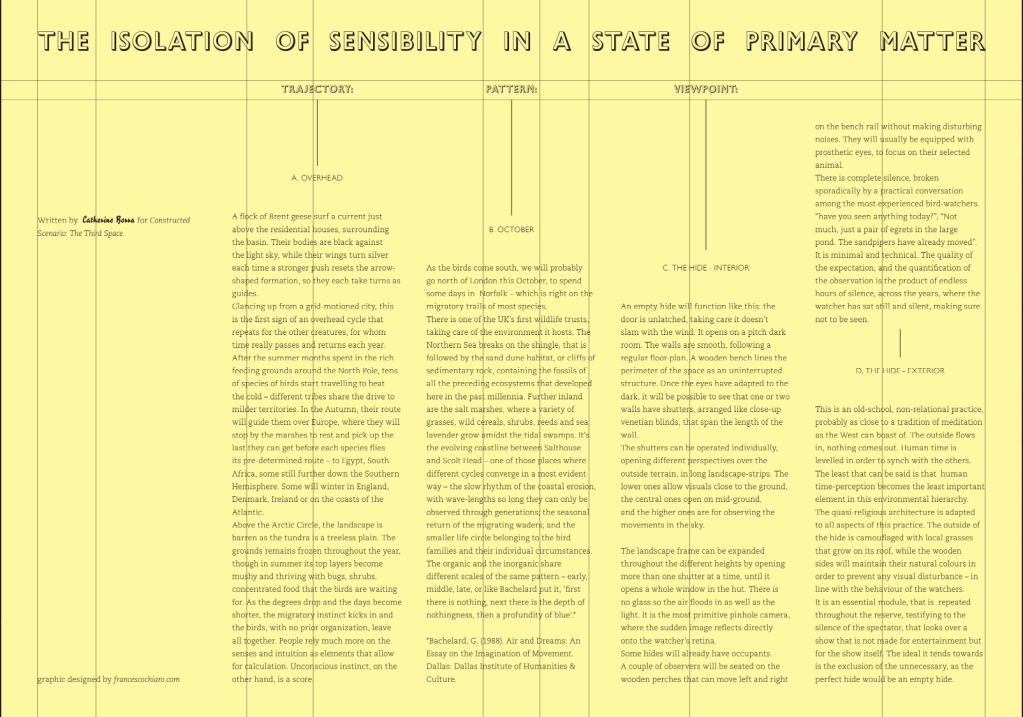

TRAJECTORY:

A. OVERHEAD

A flock of Brent geese surf a current just above the residential houses, surrounding the basin. Their bodies are black against the light sky, while their wings turn silver each time a stronger push resets the arrow-shaped formation, so they each take turns as guides.

Glancing up from a grid-motioned city, this is the first sign of an overhead cycle that repeats for the other creatures, for whom time really passes and returns each year.

After the summer months spent in the rich feeding grounds around the North Pole, tens of species of birds start travelling to beat the cold – different tribes share the drive to milder territories. In the Autumn, their route will guide them over Europe, where they will stop by the marshes to rest and pick up the last they can get before each species flies its pre-determined route – to Egypt, South Africa, some still further down the Southern Hemisphere. Some will winter in England, Denmark, Ireland or on the coasts of the Atlantic.

Above the Arctic Circle, the landscape is barren as the tundra is a treeless plain. The grounds remains frozen throughout the year, though in summer its top layers become mushy and thriving with bugs, shrubs, concentrated food that the birds are waiting for. As the degrees drop and the days become shorter, the migratory instinct kicks in and the birds, with no prior organization, leave all together. People rely much more on the senses and intuition as elements that allow for calculation. Unconscious instinct, on the other hand, is a score.

PATTERN:

B. OCTOBER

As the birds come south, we will probably go north of London this October, to spend some days in Norfolk – which is right on the migratory trails of most travelling species.

There is one of the UK’s first wildlife trusts, taking care of the environment it hosts. The North Sea breaks on the shingle, that is followed by the sand dune habitat, or cliffs of sedimentary rock, containing the fossils of all the preceding ecosystems that developed here in the past millennia. Further inland are the salt marshes, where a variety of grasses, wild cereals, shrubs, reeds and sea lavender grow amidst the tidal swamps. It’s the evolving coastline between Salthouse and Scolt Head – one of those places where different cycles converge in a most evident way – the slow rhythm of the coastal erosion, with wave-lengths so long they can only be observed through generations; the seasonal return of the migrating waders; and the smaller life circle belonging to the bird families and their individual circumstances. The organic and the inorganic share different scales of the same pattern – early, middle, late, or like Bachelard put it, ‘first there is nothing, next there is the depth of nothingness, then a profundity of blue’.*

*Bachelard, G. (1988). Air and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement. Dallas: Dallas Institute of Humanities & Culture.

VIEWPOINT:

C. THE HIDE – INTERIOR

An empty hide will function like this: the door is unlatched, taking care it doesn’t slam with the wind. It opens on a pitch dark room. The walls are smooth, following a regular floor-plan. A wooden bench lines the perimeter of the space as an uninterrupted structure. Once the eyes have adapted to the dark, it will be possible to see that one or two walls have shutters, arranged like close-up venetian blinds, that span the length of the wall.

The shutters can be operated individually, opening different perspectives over the outside terrain, in long landscape-strips. The lower ones allow visuals close to the ground, the central ones open on mid-ground, and the higher ones are for observing the movements in the sky.

The landscape frame can be expanded throughout the different heights by opening more than one shutter at a time, until it opens a whole window in the hut. There is no glass so the air floods in as well as the light. It is the most primitive pinhole camera, where the sudden image reflects directly onto the watcher’s retina.

Some hides will already have occupants. A couple of observers will be seated on the wooden perches that can move left and right on the bench rail without making disturbing noises. They will usually be equipped with prosthetic eyes, to focus on their selected animal.

There is complete silence, broken sporadically by a practical conversation among the most experienced bird-watchers. “have you seen anything today?”, “Not much, a pair of egrets in the large pond. The sandpipers have already moved on”. It is minimal and technical. The quality of the expectation, and the quantification of the observation is the product of endless hours of silence, across the years, where the watcher has sat still and silent, making sure not to be seen. Practical haiku.

D. THE HIDE – EXTERIOR

This is an old-school, non-relational practice, probably as close to a tradition of meditation as the West can boast of. The outside flows in, nothing comes out. Human time is levelled in order to synch with the others. The least that can be said is that human time-perception becomes the least important element in this environmental hierarchy.

The quasi-religious architecture is adapted to all aspects of this practice. The outside of the hide is camouflaged with local grasses that grow on its roof, while the wooden sides will maintain their natural colours in order to prevent any visual disturbance – in line with the behaviour of the watchers. It is an essential module, that is repeated throughout the reserve, testifying to the silence of the spectator, that looks over a show that is not made for entertainment but for the show itself. The ideal it tends towards is the exclusion of the unnecessary: the perfect hide would be an empty hide.

Written for the exhibition Constructed Scenario: the Third Space, London, 2012.

You must be logged in to post a comment.